My earliest memory of Jaws (1975) is from 1989, when it was shown on Swedish television. I did not watch the film, my parents argued against it, but there was a TV program about upcoming films they would show and there I saw some clips from Jaws.1 Unfortunately I do not remember when I saw the whole film for the first time, but since that first time I have watched it regularly. I know it well, and I know it is a great film about which no apologies or caveats are needed.

The acting and the interplay between the actors, and the characters, are great, the sense of space and place is vividly realised, the dialogue is natural and powerful, as well as witty, the pacing is superb, the camera work inventive and beautiful, and the editing sharp. It is also very humane, making everything feel grounded. Most of the film is about smalltown life and the people who live there. The shark itself might be a fantasy creature, but the people are effortlessly real and human. I love everything about the film, it radiates a powerful confidence which is well-earned, although as far as I can tell it was not a confidence people had on set, as the production was beset with problems and delays.

For some reason, it is also a film drenched in myths, misunderstandings, and criticism, much of which has little to do with the film itself, but with the enormous box office hit that it became. It is by default called “the first summer blockbuster,”2 often just “the first blockbuster,” it is claimed it initiated a whole new way of releasing films, that it ruined “New Hollywood,” (or, confusingly, that it was the first film of “New Hollywood”),3 and that after years of grown-up Hollywood art films, the success of Jaws brought back mainstream popcorn flicks and the era of the sequels.4

As I have written a few times before, none of these claims stand up to scrutiny. Let me briefly concern myself with the idea that Jaws was “the first summer blockbuster.” What does this mean, and what is the significance of it? We do not talk about spring blockbusters, autumn blockbusters, winter blockbusters. But summer blockbusters is a concept which for some reason is frequently talked about, and allegedly it began with Jaws. As usual, I will play my James Bond card and point out that at least three Bond films, From Russia with Love (1963), You Only Live Once (1967) and Live and Let Die (1973), had their US premieres during the summer of their respective years5 and they did very well at the box office, in particular Live and Let Die, which opened in June and was the most successful Bond film since Thunderball (1965). Why is not Live and Let Die considered a summer blockbuster? In which sense is Jaws different, other than that even more people watched it than any of the Bond movies? Other notable summer releases of that time were Rosemary’s Baby (June 1968), Easy Rider (July 1969), Shaft (June/July 1971), and Deliverance (July 1972).

If you look at American box office charts of the 1970s, you do not see any changes before and after 1975 regarding which kinds of films were popular. 1974 had three disaster movies and three sequels in the top ten,6 so it is not obvious what glory days Jaws supposedly ruined. It is however more common that top ten box office successes were released in the summer towards the end of the 1970s than had been the case before. Several films of the kind that would previously have been released towards the end of the year, or in March/April, would now be released in June/July/August. But what is it about the summer that makes blockbusters released then more interesting? Why does it matter so much to critics and scholars whether such a film is released in June instead of November? Either way, Jaws was not first.7

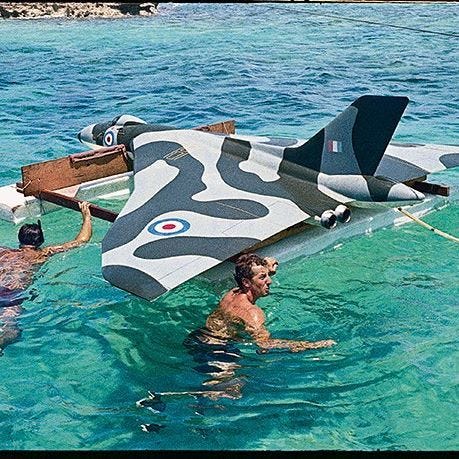

Another recurring claim is that Jaws was “the first major motion picture to be shot on the ocean.”8 I do not know what this means either, as many films have been shot on an ocean before 1975. They Were Expendable (1945), Moby-Dick (1956), In Harm's Way (1965), and Juggernaut (1974) are some titles I immediately thought of when writing this paragraph. And as always there is a Bond film, this time Thunderball, of which a large part was shot in the green water outside the Bahamas.

The immense box office successes of The French Connection (1971), The Godfather (1972), and The Exorcist (1973) have rarely, if ever, been held against them, as the success of Jaws has been held against it. Yet I have always considered Jaws as belonging to that group of exceptional genre films of that time, that received a new level of attention within their respective genres. Although, which genre Jaws belongs to, or if it belongs to any particular genre, is a relevant question. Today it is often called a horror film and when it came out many critics considered it as part of the cycle of disaster films that were dominating the box office the years before 1975. Personally, I am not sure Jaws belongs in either, but maybe more of a disaster film than a horror film.

These films, Jaws, The French Connection, The Godfather, and The Exorcist, stood out in the public and critical consciousness when they were released, and continue to do so, in a way few other films of similar genres had done. The reason for that is not just that they were remarkably well-made but that they also were such box office sensations, and because they came about at the time that they did, as it is a mythical era. Though they are not better than many other films from these years such as, to name two obvious examples, Charley Varrick (1973) or The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973). But these two films had nowhere near the same visibility or name-recognition, and certainly not now.9 Presumably because they did not dominate at the box office in the same way as those others.

As mentioned above, a group of films that did dominate at the box office were the disaster films, such as The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Airport ‘75 (1974), Earthquake (1974), and The Towering Inferno (1974), but as these are of considerably less artistic value than either of the films in the previous paragraph, they are rarely discussed or analysed today, and there is no reason for why they should be, but it is still curious which films live on, and matter beyond their peers, and which films do not.

But enough of facts and figures. Jaws is a superior film that gets nothing wrong; everything works beautifully. We are lucky to have it, and to be able to rewatch it, and forget all the nonsense that have been said about it. Maybe its remarkable success has allowed people to take its qualities for granted, instead of being continuously marvelled by them.10

A peculiar thing is that for some reason I watched that program twice, its original broadcast and a rerun the next day. What is more peculiar is that the film clips shown from Jaws were not the same on the rerun as on the original broadcast. What’s up with that?

As in a recent article about Jaws in Financial Times.

Some refer to the period 1967 to 1980, from Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate to the financial disaster of Heaven’s Gate, as “New Hollywood.” Others, as I mentioned, think “New Hollywood” is 1967 to 1975, i.e. until Jaws only. And others consider the post-Jaws era as “New Hollywood.” Neither of these classifications make much sense, and I do not understand why anyone thought it was a good idea to use the same term to refer to three different time periods.

Jaws 2 (1978) is remarkably similar to Jaws, and the cinematography is very beautiful, but it is a dull, uninteresting, flat film. I think we can assume this is because it was directed by Jeannot Szwarc, and not Spielberg. Both films are co-written by Carl Gottlieb, who also wrote a book about the making of the first. He has for some reason not written a book about the making of the sequel.

To be specific, From Russia with Love opened in December 1963 in the UK, but then had its US premiere in June of 1964.

The US top ten films of 1974 were 1) The Towering Inferno, 2) Blazing Saddles, 3) Young Frankenstein, 4) Earthquake, 5) The Trial of Billy Jack, 6) The Godfather: Part II, 7) Airport 1975, 8) The Longest Yard, 9) The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams, and 10) Murder on the Orient Express. (A good year for Mel Brooks as well as for disasters.)

Blockbusters was an established concept already in the late 1940s, of a certain kind of films that were expecting to do, or did do, remarkably well at the box office. I think the first film that was called a blockbuster in the same way we use the term today was Samson and Delilah (1949). If you persist in calling Jaws the first blockbuster you must explain why all the previous Bond films and disaster films and action films and horror films and epics and so on and so forth were not blockbusters, and also explain why such films and Bond films made after Jaws suddenly became blockbusters.

That exact quote was from Wikipedia's page for Jaws, but the idea appears in various books and articles.

Don Siegel and Peter Yates directed them, among the best of their careers. Worth pointing out that Peter Yates, before The Friends of Eddie Coyle, also directed Bullitt (1968). It is one of the best American films of the late 1960s yet rarely talked about in such a way. Yates was once a great filmmaker, at least from Robbery (1967) until the early 1980s. Then he lost his way somewhat, and I would not recommend his first film Summer Holiday (1963) either, unless you are a hardcore Cliff Richard fan. But he deserves to be watched and studied more than he is.

Those were the days when such a film was not even the best of the year. From this particular year, I would rate Dog Day Afternoon as the best American film.